- DateJuly 2015

- LocationColesbutka, Svalbard

- CategoryExpedition

- TeamAlexander Pyka & Jonathan Danko Kielkowski

- Text & ImagesJonathan Danko Kielkowski

From Barentsburg to Longyearbyen 2/3

Svalbard | Expedition | July 2015

Arctic Coal Episode 7

- Halfway between mainland Europe (600km south) and the North Pole (1000km north) lays a archipelago called Svalbard. Formed by over 400 islands, shaped by glaciers and surrounded by the Arctic Ocean which penetrates uncountable fjords is home for more polar bears then humans. And so the need to carry a rifle is necessary as soon as one leaves town into the wild where no streets nor trails, no cars or trees can to be found. In summer 2015 Alexander Pyka and myself went on an adventure to this remote place to document the remains of Svalbards once glory mining industry.

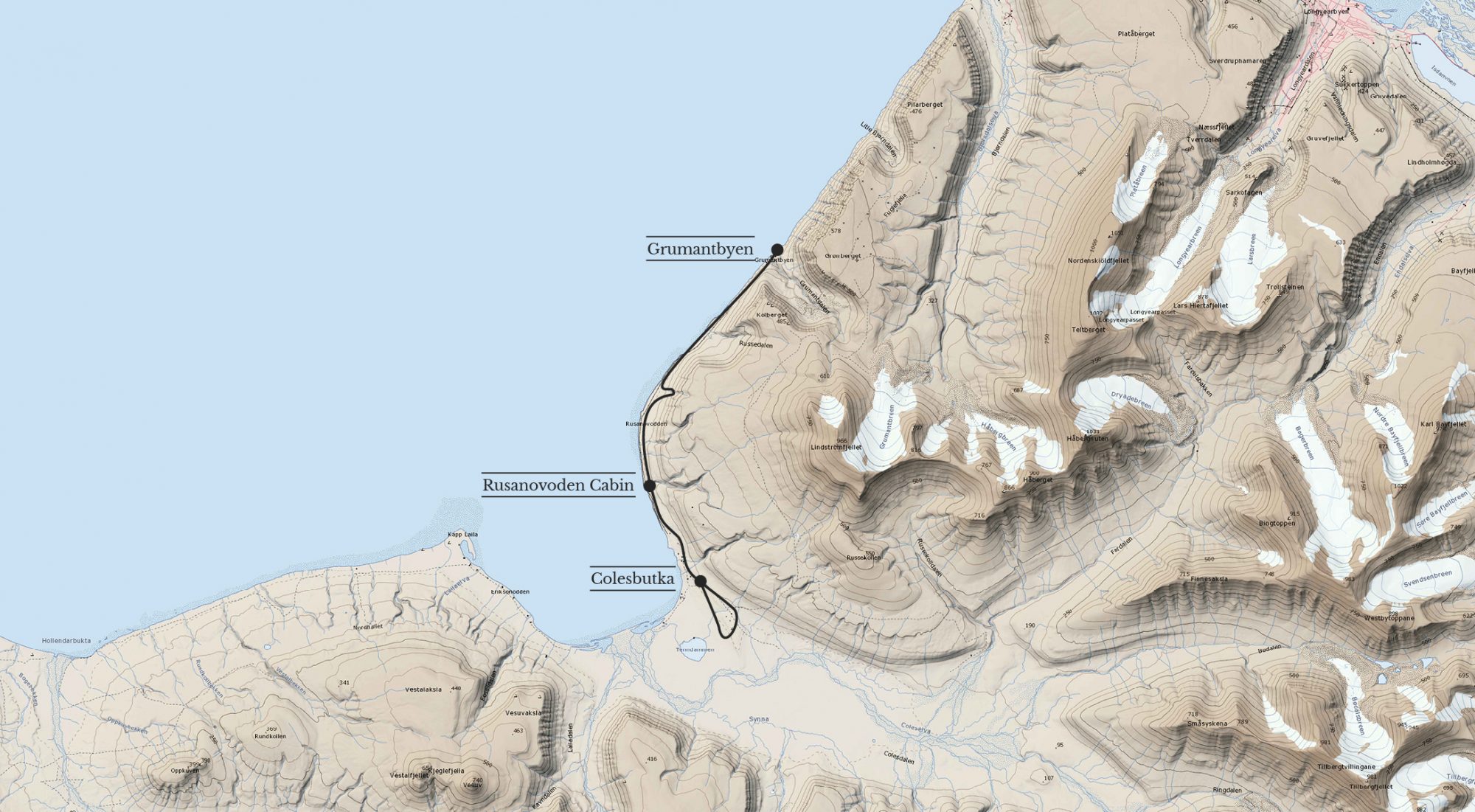

After being stuck with two slightly shitty options to get out of Grumantbyen and to the Rusanovodden Cabin, we chose the one that seemed to be the least shitty one to us

Leaving Grumantbyen

As low tide kicked in, we took off walking on the beach along the cliffs. To make the 8 km to Colesbutka before high tide, we needed to walk fast. The beach looked nice and smooth and so we were quite confident this would be a no brainer.

But after a few hundred metres, the beach became an obstacle course consisting of slippery rocks in all sizes. Trying to keep our walking speed with our 35 kg backpacks led to painful slips and falls. We needed to slow down. Hope that the terrain would become friendlier to walk on again soon, kept us going. But before it did, we had lost so much time that we found ourselves in a situation realising we would neither make it to Colesbutka nor back to Grumantbyen before high tide would cut our way off. Exhausted and stressed, we were looking for a spot to climb up along the 10 to 20 meter high cliff. Just before our way was cut off by rising water, we found our perfect spot.

The waterfall and the river above had washed out and caved into the cliff. At its lowest point, the cliff was only 5 metres high. The surface of the cliff at this spot was very rugged, which made it much easier to climb up. Pyka was the first one to go: he made it up, hoisted up our backpacks with a rope and then it was my turn.

Remains of the Grumantbyen-Colesbutka Railroad Line

- HistoryThe Grumantbyen-Colesbutka narrow-gauge railway connected the two Russian settlements Grumatbyen and Colesbutka. Built in the years between 1926 and 1932 it was Spitsbergen’s longest surface railway with its 8km length, much of which was sheltered in a wooden construction against winter snowdrift. Its main purpose was to transport coal from the Grumantbyen mine to the new established port town Colesbutka. It had several bridges and entered the Gruamntyben bay through a 300 metre long tunnel. The line was abandoned along with Grumantbyen and Colesbutka in the year 1965.

As we climbed up the cliff, we finally had smooth ground under our feet. The stress and the pain from the last hours were now rewarded with a panorama view from the cliff over the fjord.

To make it even better and to our surprise, the remains of the railroad line were still well preserved and visible. Despite the destruction prior to the departure of the Russians and the decay from the past years, the train tracks were still there, wagons were scattered along the way and even long parts of the wooden construction were still intact.

From here on, we were able to walk the rest of the way on the railway tracks and soon after that, we had arrived at the Rusanovodden Cabin. It was already 4 a.m. and the only thing we could think of was finally getting some sleep.

The Rusanovodden Cabin

- HistoryThe Rusanovodden Cabin was built in 1912 by Vladimir Aleksandrovich Rusanov, 1875-1913, a Russian geologist and explorer who claimed the property at Grumantbyen in 1912. After his death in 1913 and the start of Russian coal mining activity in this part of Svalbard, the cabin was turned into a small self-guided museum in honour (BE) of Rusanov. The cabin is one of the few open to the public on Svlabard today. Besides the museum, it also offers beds for up to 6 people, a stove and basic cabin equipment.

Reaching the Cabin after being awake and on our feet for almost 24 hours was a huge relief. We finally took a long break without being paranoid about polar bears, made some lunch and set up a fire inside the stove. As the fire started to heat up the cabin, we got comfortable inside the wooden beds and soon fell asleep for the next 15 hours.

Colesbutka

- HistoryColesbukta was originally a whaling station. Later in the early years of the 20th century first coal mining attempts in the bay itself were made but were soon canceled and relocated. Coal mining activity started in the nearby new founded settlement Grumanbyen. Due to shallow waters around Grumantyben, it was not possible to pick up the coal by ships. The attention focused on Colesbutka again which was more suitable for a port. Operations stared in the year 1932 and ended with the closing of the Grumantbyen coal mine in the mid 60s. Until 1988, Colesbutka did serve as a Russian base for exploratory coal drilling and was later abandoned.

From the Rusanovodden Cabin it is only a 10 minute walk on the railway path to Colesbutka. We left our heavy equipment inside the cabin, grabbed only our cameras and our rifle and headed towards the port town.

The railway tracks soon disappeared after leaving the cabin and the Colesbutka came in sight.

Similar to Grumantbyen, all the industrial buildings in Colesbutka were destroyed. We were greeted by twisted steal beams and broken concrete blocks that belonged to a now unrecognizable building. It looked almost like a modern piece of art. Debris were scattered around the ruin and even found over a hundred metres away from the site indicating that the explosion that ripped apart this building must have been very powerful.

We found a half sunken ship at the dock together with some mining equipment that was left in the port. Wood, barrels and other debris covered the beach around the settlement.

The old Colesbutka power plant was turned into a hollow façade. The entire interior, all the machines, cables and anything with value had been removed or dismantled. Toxic waste and trash on the other hand, had been left behind.

In contrast to the destroyed infrastructure and industrial buildings, the residential buildings were still not only recognizable but also in a rather good shape. A lot of the interior still was at its place and some of the rooms looked like it had only been a few days ago that they were used last.

The beds were made, food was in the kitchen and a lot of personal belongings could be found on the tables or inside the cabinets. It went to a point where we weren’t actually sure if someone was still living there!

But apart from birds and reindeers, we couldn’t find any other living inhabitants in this town.

What we did find was an old graveyard. About 20 bodies still lie here. They are the bodies of young coal miners who had lost their lives in this remote part of the world. Some of the gravestones show pictures of the men’s faces.

After four hours in Colesbutka, we decided to head back to our cabin.

Instead of enjoying the evening and resting before our long hike back to Longyearbyen, we got some bad news that crossed our plan and that made everything a bit harder that it already was anyway…

Continue to Part 3

- Arcitc Coal Episode Index

- Intro Arctic Coal

- Longyearbyen Coal Crane

- Longyearbyen Gruve 2

- Longyearbyen*

- Barentsburg

- From Barentsburg to Longyearbyen Part 1 Grumantbyen

- From Barentsburg to Longyearbyen Part 2 Colesbutka

- From Barentsburg to Longyearbyen Part 3 Drill Rigs

- Pyramiden*

- The Pyramid*

- *not published yet

Hi – I wonder why you walked on the beach instead of following the railroad track. Is it because the railroad do not go the whole way to Grunant?

I have just returned from Svalbard, and was walking from Colesbutka towards Grunant, but because a fellow from Taiwan, who I had allowed to join me, was very slow and tired, I took the shortest route back to Longyearbyen by going up Russedalen and missed out on Grunant.

Next time on Svalbard, I would like to do Longyearbyen – Fuglefjellet – down through Grunant Valley to Grunant and follow rail road to Colesbukta and from there continue to Barentsburg.

Hey hi Jens thanks for your comment.

The last part of the tracks leads through a tunnel that is collapsed today. This means you have to walk up the mountainside in order to get in our out to Grumant.

Since we had a lot of heavy equipment we thought it would be easier to walk along the beach.

But this turned out to be a bad idea (as described in the text) I would recommend to walk as long as possible along the tracks and enter/exit Grumant over the mountainside.

Let us know when you will be there the next time. Would be cool to hear how it was for you and if the place changed since we were there the last time 🙂